Eastern Europe Comfort Food for Cold Seasons: A Shared Language of Warmth

Cold seasons in Eastern Europe is not merely a season, it’s a whole experience. It’s the quiet crunch of snow under boots, the warmth of woodsmoke curling from chimneys, and the scent of something hearty simmering on the stove. Across Russia, Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and beyond, comfort food isn’t just about taste; it’s a language of survival, memory, and love. When the air grows sharp and daylight shortens, our tables fill with dishes meant to warm body and soul: cabbage soups, potato pancakes, dumplings, and slow-cooked stews. Each region adds its own accent, but the message is the same; come in, sit down, and eat.

From Russia with Warmth

I grew up in Russia, where winter rules half the year. Here, food has always been practical, born of necessity yet rich in tradition. What our ancestors salted, baked, and fermented, we still make today. Rye bread, sauerkraut, mushrooms, and pickles; these are not just ingredients but artifacts of our climate and culture. To eat them is to remember those who came before us.

My grandmother’s kitchen was my first school of warmth. I still recall trudging home through the snow after school, my scarf frozen stiff, when the smell of pirozhki would reach me from the stairwell. She fried them simply, filled with mashed potatoes and onions, golden and crisp. The recipe is simple, but the main ingredient of the family dish – love. Without it, the food turns out to be “bland”. They were small, but their magic was immense. The first bite thawed the day away. I once traded them at school for keychains and a soccer ball; later, I sold a few to buy her medicine and flowers for my mother. Those pies taught me that food is both currency and connection; a way of giving, even when you have little.

The Russian Winter Table

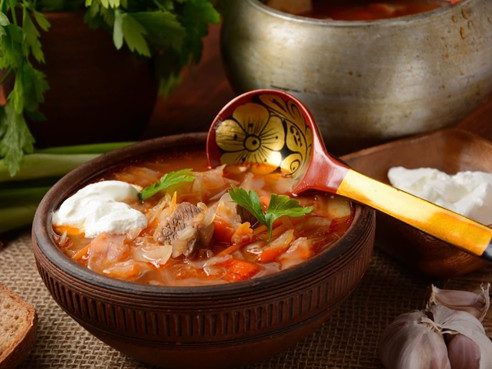

In Russia, winter tables are generous but grounded. Shchi, our cabbage soup, has fed peasants and poets alike for centuries. It’s ladled with sour cream and served with rye bread, often the first thing placed before guests. The saying goes, “Shchi da kasha — pishcha nasha” — “Cabbage soup and porridge are our food.” It captures our soul perfectly; simple, sustaining, and communal.

Another favorite is pelmeni, Siberian dumplings that every family makes in its own style. In my house, making pelmeni was a family ritual. We’d gather around the kitchen table; father, mother, me, and shape tiny dumplings by hand. Dad’s were lopsided, Mom’s had a delicate jeweler’s crimp, mine were clumsy, but each had its mark. They’re small, but they remind you of what matters: we’re different, yet we’re one family.

Once done, we carried trays of them to the balcony, our natural freezer, where they would harden in the −20°C night. All winter, we’d boil them as needed, topping them with sour cream or vinegar. Even now, whenever I make pelmeni with others, I feel the same quiet joy, kneading dough together as snow falls outside.

A Taste of Slovakia: Michal’s Winter Memories

But Russia isn’t the only country where winter brings people closer through food. A friend from Slovakia, Michal Kadubec, who lives in a small village called Likavka, says that when the weather turns cold, their kitchens come alive with potatoes and cabbage, the humble stars of the Slovak pantry.

His favorite dish is zemiakové placky, crisp potato pancakes made right after the harvest, when potatoes are fresh from the earth. “When we were kids, we helped dig them up,” he recalled, “and while we played in the garden, our parents fried placky inside. The smell, it was pure home.”

Slovakia’s comfort food shares much with Russia’s; hearty, smoky, and full of earth’s flavors. Dishes like kapustnica (cabbage soup with sausage, mushrooms, and smoked meat) are staples of the winter season. Every family has its version; some add dried plums, others garlic or sour cream. It’s the kind of dish that fills a house with its aroma and a heart with nostalgia. Michal says their winter also marks the traditional pig-slaughtering season—zabíjačka—when communities come together to make sausages, bacon, and blood sausages like krvavničky and jaternice. Nothing goes to waste; it’s a celebration of self-sufficiency.

Festive Traditions and Family Rituals

At Christmastime, Slovak tables shine with ritual. There’s always a thin wafer with honey to begin, then sauerkraut soup made from the juice of fermented cabbage, fried carp with potato salad, smoked fish, fruits, nuts, and cakes. When the cold deepens and snow begins to fall, the meal often ends with a glass of slivovica, a homemade plum spirit cherished across the Balkans.

One beautiful custom struck me: they always leave an empty plate at the table for a traveler. “It’s a reminder that no one should be left hungry,” Michal said. That spirit of hospitality is something all Eastern Europe shares. Whether in a Slovak mountain home or a Russian dacha, guests are sacred.

In Russia, Christmas follows a familiar rhythm; first with the family, then with the world.

After prayers and kutya at home, the night spills into the streets, where people share mulled wine, sweets, and laughter with strangers. One time, my friend and I did the same, wandering snowy parks and trading treats. We even met a girl crying in the cold. Turned out she was robbed and heartbroken. So we sat with her, shared wine and cookies, and soon she was smiling again. That night I realized Christmas isn’t just about food; it’s about warming hearts, and human connection.

Across Borders: A Winter Feast of Cultures

Traveling through Eastern Europe in winter means tasting how people keep warm through centuries of cold.

In Poland, bigos, the hunters’ stew of sauerkraut and meats, simmers for days; in Hungary, its paprika-rich cousin, gulyás our goulash, tells a similar story in a different tongue. Romania serves sarmale, cabbage rolls stuffed with rice and meat, adn you’ll find their twins, sarma, in Serbia and Bulgaria, each with its own spice and soul.

The Czech Republic comforts with svíčková, beef in creamy vegetable sauce, while Slovakia’s bryndzové halušky, potato dumplings with sheep cheese and bacon. It feels like snow-day sustenance. Farther east, borscht and pelmeni appear across Ukraine and Russia, shifting slightly with each border but always bringing warmth.

Down south, the Balkans fill the air with grilled ćevapi and slow-cooked pašticada, while in Slovenia, jota, a stew of beans, sauerkraut, and pork, carries the same rustic spirit. And as you near the Baltics, cepelinai and grey peas with bacon remind you that in this region, the names may change, but the comfort never does.

Where to Taste Authentic Winter Cuisine

When travelers ask me where to experience true Eastern European comfort food, I tell them to skip the fancy city restaurants and seek the smaller places; the kolibas in Slovakia, traktirs in Russia, or local taverns in Poland.

In Likavka, Michal recommended to go to Koliba Likava, Koliba u Dobrého Pastiera, and Salaš Krajinka, cozy wooden inns where you can taste kapustnica and lokše (thin potato pancakes served with duck or sweet fillings).

In Russia, I send friends to Moscow’s must-try spots for Russian cuisine, and here are a few tips you can hardly go wrong with. The prime season for bliny is Maslenitsa, when almost every place expands its menu. But the best way to try bliny is at the city fairs, you’ll get the true homemade taste. Another great option is “Bliny na Taganskoy,” a living time capsule and one of the oldest authentic Soviet-style stolovaya: they’ve been frying bliny for over 60 years, and the samovar-filled interior and classic recipes have barely changed.

If you’re short on time on your last day, any major bliny café chain will save you, quick and tasty. Pelmeni with vodka are a ritual of their own for travelers. Drop into any “Ryumochnaya” in or around the center: many are styled after the late 19th–20th centuries and serve homemade pelmeni. Prices are modest and the food is excellent. As we say—na zdorovye!

At Christmas markets across Prague, Kraków, or Bratislava, follow the smell of roasting chestnuts, mulled wine, and sizzling pancakes, culinary warmth served straight from wooden stalls.

A Spirit That Keeps You Warm

Traveling through Eastern Europe in winter means slowing down and savoring life’s simplest comforts—sharing food, warming hands, and waiting for spring. Whether it’s tea or medovina in Slovakia, a shot of vodka in Russia, or pierogi in Kraków, warmth is always close at hand. These flavors are more than recipes; they’re memories and traditions that turn even the coldest season into one of generosity, connection, and quiet joy.

Vladislav Zherko

WriterI write from Moscow, a city where history hums beneath every streetlight and the rhythm of modern life never quite drowns out the echoes of the past. My stories grow from this intersection: where centuries-old traditions meet restless creativity, and where every journey through Russia reveals something unexpected. Through my writing, I hope to show that Russia is not just vast in distance, but in spirit — a country of contrasts, resilience, and quiet beauty waiting to be discovered in the details.