Rescuing More Than Animals: How a Jogja Wildlife Center Is Pushing Back Against Greed

When a new highway cut through the land of Wildlife Rescue Centre Jogja, the move was more than a logistical disruption — it was a stark reminder of the forces reshaping Indonesia’s landscapes. For years, the center has treated animals rescued from the country’s vast domestic wildlife trade, many arriving injured and far from their native habitats. But as forests continue to disappear by the hundreds of thousands of hectares each year and illegal trafficking persists, WRC Jogja has come to realize that rescue alone is not enough. Their story is not just about rehabilitation. It is about confronting greed, redefining conservation, and rethinking what responsible tourism should mean in a biodiversity-rich nation under pressure.

Rescue Center in Transition

Before any bulldozers arrive, the grounds of Wildlife Rescue Centre Jogja (WRC Jogja) are already quieter than they used to be. The familiar morning rounds—checking cages, cleaning wounds, tending injuries, coaxing frightened animals to eat—have largely fallen away.

A new highway project has been approved, and its planned route cuts directly through the centre’s land—the sanctuary that has served as WRC Jogja’s operational base for nearly two decades. Construction has not yet begun. No heavy machinery has arrived. Yet, in practice, the centre has already been forced to stop.

Since 2022, WRC Jogja has lived in transition—relocating to a larger site, waiting for permits, and redistributing animals across Indonesia’s conservation network. Some have been released back to the wild. Others transferred to partner rescue centers. A few are temporarily housed in zoos. The pause is logistical. But the story behind it is larger—and more unsettling.

Jogja As a Domestic Wildlife Transit Point

Yogyakarta or Jogja is known globally for Borobudur and Prambanan, batik workshops, and student life. Far less visible is its role as a domestic wildlife transit point.

Most of the animals arriving at WRC Jogja are not bound for overseas markets. They circulate within the country—moved from forests in Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, or Papua into Java’s dense urban markets. Java, home to more than half of the nation’s population, has become a major consumer base for exotic pets and songbirds.

According to monitoring by TRAFFIC and Indonesian authorities, thousands of protected animals are seized each year—and seizures likely represent only a fraction of the real trade. The illegal wildlife economy remains one of Southeast Asia’s most persistent environmental crimes.

By the time animals reach Jogja, many of them are often already damaged. We met Cisca Nurfi’aini, Operations Manager at Wildlife Rescue Centre Jogja, in Jogja, where she kindly took the time to share the centre’s story. “The animals come with their own wounds,” Cisca said. “Physical and mental.”

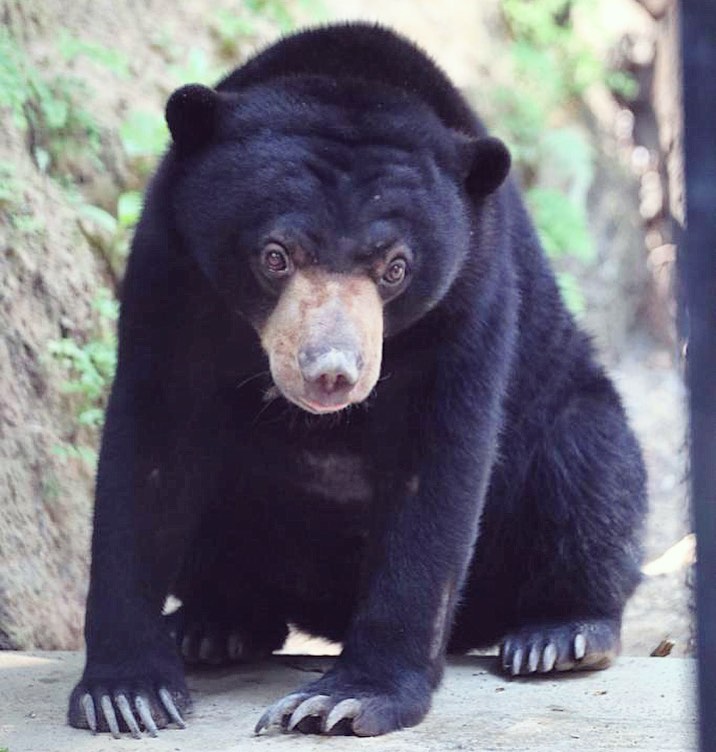

Primates arrive malnourished or chained. Birds come with clipped wings. Reptiles are severely dehydrated. Some species are exceptionally sensitive and highly stressed in captivity. Among the most fragile is the Javan pangolin—locally known as trenggiling—a species listed as Critically Endangered and notoriously difficult to rehabilitate because of stress and highly specialized dietary needs. Rehabilitation, here, is never a simple reversal.

A Country Losing Its Forests

Indonesia remains one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth — home to around 10% of the world’s plant species, 12% of mammals, and 17% of bird species. Many are endemic.

Yet habitat loss continues.

In the past decade, Indonesia has lost hundreds of thousands of hectares of forest each year. Although deforestation rates have fluctuated and declined compared to peak years in the mid-2010s, annual forest loss has still remained significant due to agriculture expansion, mining, logging, and infrastructure projects.

Forest loss and wildlife trade feed each other. As habitats shrink, animals become easier targets. As roads extend deeper into forest frontiers, extraction becomes more efficient.

The same development logic that carved a highway through WRC’s former site is reshaping ecosystems across the archipelago.

The Limits of Rescue

WRC Jogja was originally focused on rehabilitation: treat, stabilize, release. But many of the animals confiscated in Java are not native to Java. Releasing them locally would disrupt ecosystems. Returning them to their original habitats requires inter-provincial coordination, permits, ecological assessment, and funding.

Some species are highly sensitive to environmental changes. Others, after long captivity, struggle to regain survival instincts. Rehabilitation can take months or years. Sometimes it fails.

Over time, the team realized rescue alone does not solve the problem. “If we keep rescuing without education, it never ends,” Cisca explained.

Illegal trade is driven by demand. It is normalized by social media trends, by status culture, by the perception that wild animals are commodities.

The rescue center began to see its work not only as saving individuals, but as restoring ecosystems and awareness — a far larger challenge that requires communities, policy reform, and cultural change.

The Long Fight of Malayan Giant Turtle

One species now set to become a priority at the new location is the Malayan Giant Turtle (Orlitia borneensis). In 2003, authorities confiscated 19 individuals from the illegal pet trade and placed them at WRC Jogja. For years, they remained part of the center’s residents. In 2018, during a full animal disposal assessment, the team made an unexpected discovery: the population had grown to 40 individuals. Some had successfully bred in captivity.

The Malayan Giant Turtle is distributed across Peninsular Malaysia and parts of Indonesia, but its population has collapsed across much of its range. Recently classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, the species has declined by at least 80% over the past 90 years. Poaching and habitat loss are its greatest threats.

With limited resources, WRC Jogja cannot take in every species. At the new site, the team plans to focus more strategically — and the Malayan Giant Turtle rehabilitation and conservation program will become one of its top priorities.

Learning to say no, in conservation, is sometimes necessary to say yes more effectively.

Rethinking Tourism’s Role

Before relocation, WRC Jogja hosted international volunteer programs. Volunteers joined one- or two-week stays, assisting with feeding, cleaning, and daily care. Volunteer fees were one of the main funding sources. These programs significantly helped cover daily operational costs. They also provided something intangible: direct exposure.

For many volunteers, it was a rare opportunity to encounter wildlife up close — not as entertainment, but as victims of exploitation. They learned about animal behavior, stress responses, and the long road of rehabilitation.

Partnerships mattered too. Superindo, a major supermarket chain in Jogja, regularly supplied surplus fruits and vegetables — near-expiry produce still safe for animal feed — reducing waste while supporting conservation.

Since 2022, volunteer programs have been on hold due to relocation and permit delays. This pause reveals a bigger tension in tourism. Responsible travel can help fund conservation, but conservation cannot rely only on a steady stream of visitors. If we talk about a “Great Reset” in tourism, it has to mean building systems strong enough to survive even when tourists stop coming.

Fighting Back

The story of WRC Jogja is not just about injured animals. It is about resistance — against a culture that commodifies wildlife, against development that fragments habitats, against the normalization of keeping wild creatures as pets.

The highway that displaced the center symbolizes Indonesia’s rapid transformation. Roads promise growth. Markets expand. Consumption rises.

But in a conservation facility rebuilding itself from disruption, a small team continues to argue — through care, education, and difficult strategic choices — that growth without ecological limits is self-destructive.

If tourism is to redefine its future, especially in biodiversity-rich countries like Indonesia, it cannot focus solely on numbers of visitors. It must ask harder questions:

What kind of mobility are we supporting?

What landscapes are we reshaping?

What lives are displaced in the process?

The animals that once filled WRC Jogja’s old enclosures are now scattered — some back in forests, some under care elsewhere, some waiting for release.

Their survival does not depend on sympathy. It depends on whether communities, industries, and travelers are willing to confront the systems that put them in cages in the first place. That confrontation — uncomfortable but necessary — may be the real reset.

💡How you can help

Wildlife Rescue Centre Jogja (WRC Jogja) survives through public support and collaboration. For now, while the centre is in the midst of relocation and most of its programmes remain on hold, there are still a few simple ways you can continue to support their work on the ground:

- Donation

- Partnership

Contact:

📧 info@wrcjogja.org

Deti Lucara

Writer | FounderI’m a writer and traveler from Indonesia, and the founder of thecharmingworld.com — a space born from my love for art, culture, and human connection. I created it for kindred souls who believe that beauty lives in curiosity, wonder, and the stories we share along the way.