What Giza Teaches Us About Climate and Power

The Great Pyramid of Giza is often framed as a triumph over nature: a geometric mountain rising from a hostile desert, defying heat, wind, and time. But look closer, and a different story emerges. The pyramids were not built in spite of the environment—they were built because of it. Their construction moved in rhythm with the Nile, dependent on climate stability and shaped by earlier environmental change. In today’s era of “Great Reset,” as climate systems grow less predictable, Giza offers a clear lesson: enduring achievement does not come from conquering nature, but from aligning ambition with it.

A Desert Chosen on Purpose

By the time the Great Pyramid was constructed (around 2580–2560 BCE), the Giza Plateau was already arid. The era of the “Green Sahara”—when North Africa supported lakes, grasslands, and pastoral communities—had ended thousands of years earlier. Desertification gradually pushed populations toward the Nile Valley, concentrating life along a narrow corridor of fertility.

The plateau itself was dry, rocky, and elevated—ideal for monumental construction. It offered:

- Stable limestone bedrock.

- Protection from annual Nile flooding.

- Clear visibility across the floodplain.

- Proximity to transport routes.

In other words, the pyramids were positioned deliberately between two worlds: the fertile, life-giving Nile Valley and the eternal stillness of the desert. Life thrived by the river. Eternity was staged in stone beyond it. The setting was not random, it was environmental strategy.

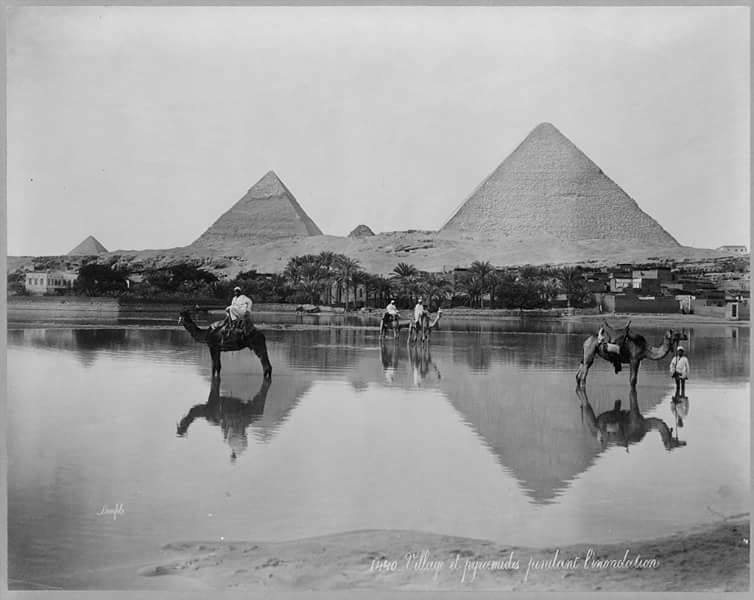

The Nile as Construction Engine

If the desert provided permanence, the Nile provided possibility. Ancient Egypt’s entire economic and political system was built on the annual inundation. Each year, between roughly June and September, the Nile overflowed its banks, depositing nutrient-rich silt across agricultural fields. During these months, farming paused.

This pause mattered enormously.

The same farmers who planted and harvested during the dry season were available during inundation to participate in state projects. Archaeological evidence—including workers’ villages near Giza—suggests organized, rotating labor crews rather than enslaved masses. These crews were fed with grain from surplus harvests made possible by stable flood cycles.

The river created:

- Predictable agricultural surplus.

- Seasonal labor availability.

- Efficient water transport for heavy materials.

Without reliable floods, no surplus. Without surplus, no workforce. Without workforce, no pyramid. The monument was a byproduct of hydrological stability.

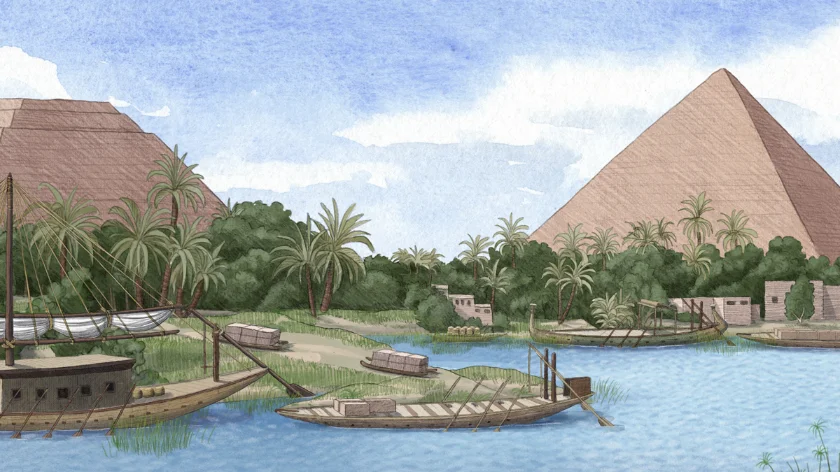

Riding the Flood

Recent geological research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022) indicates that a now-diminished branch of the Nile once ran much closer to the Giza Plateau. This channel likely functioned as a logistical artery, allowing barges to transport limestone and granite directly to the construction zone.

During flood season, higher water levels expanded navigable routes. Massive limestone blocks from nearby quarries and fine Tura limestone for casing stones were floated across water, not dragged endlessly across sand. Granite beams from Aswan—hundreds of kilometers upriver—traveled downstream along this same watery network.

The Nile was not just a background feature. It was a supply chain.

Ancient Egyptian officials, such as Merer (whose administrative papyri were discovered at Wadi al-Jarf), recorded transporting stone via river systems connected to Giza. These documents reveal an organized, river-dependent infrastructure.

Climate Stability and Political Power

The Old Kingdom flourished during a period of relatively stable Nile flooding. That stability allowed long-term planning on a monumental scale.

But climate in ancient Egypt was not permanently secure. Toward the end of the Old Kingdom, prolonged episodes of low Nile floods contributed to famine, decentralization, and political fragmentation. Monumental construction slowed dramatically.

This correlation between environmental fluctuation and state power offers a subtle but critical insight: the pyramids were built during a window of climatic reliability.

They symbolize permanence—but were made possible by predictability. When environmental rhythms faltered, so did centralized authority. This is not just ancient history. It is a pattern repeated across civilizations.

Engineering with Nature, Not Against It

Modern narratives often portray the pyramids as feats of brute force. Yet what emerges from environmental context is something more nuanced.

Construction likely followed seasonal rhythms:

- Flood season: Mobilize large labor crews; transport heavy materials by boat.

- Dry season: Resume agriculture; continue precision stone placement and internal chamber work.

Rather than resisting the Nile’s cycles, pyramid construction synchronized with them. Environmental timing was not an obstacle—it was an asset.

This distinction is critical. Ancient Egypt did not attempt to overpower its primary ecological system. It structured its labor, economy, and cosmology around it. The pyramids represent not defiance of nature, but alignment with it.

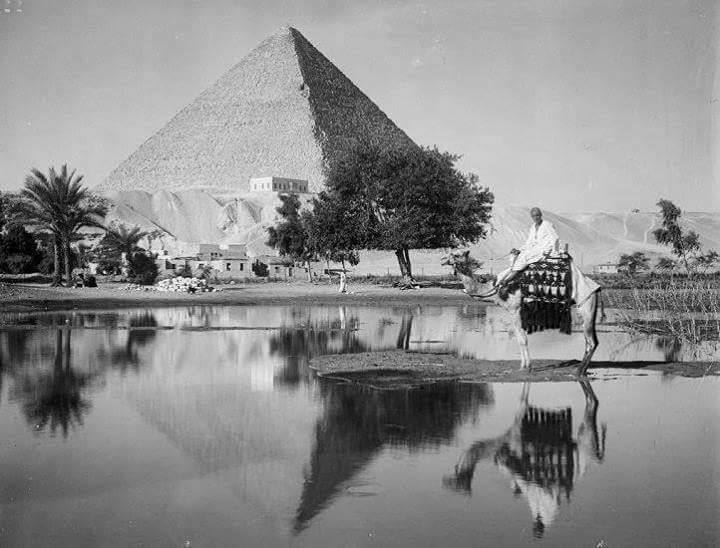

The Desert as Preserver

One reason the pyramids endure is environmental. The arid climate of the Giza Plateau slows biological decay. There is minimal vegetation to break apart stone, little rainfall to chemically erode surfaces, and relatively stable conditions over centuries.

Compare this with tropical climates, where humidity, roots, and monsoon cycles aggressively deteriorate architecture. In Egypt, sand may bury—but it rarely rots.

The Sphinx, for example, was periodically buried by windblown sand, yet this burial also protected it from some erosion.

Desert does not nurture life easily. But it preserves memory well. The pyramids were placed in a landscape that would guard them.

Reading Giza Through a Climate Lens

The Great Pyramid has survived for over 4,500 years. Yet its existence is inseparable from environmental conditions that enabled it. It was built in a carefully chosen arid zone, supplied by a river whose rhythms shaped labor, economy, and power.

In an era when climate variability is again reshaping societies, Giza offers a paradox: Human ambition can reach extraordinary heights. But it does so most effectively when aligned with environmental systems rather than in opposition to them.

The pyramid may appear to conquer the desert. In truth, it was the river that made it possible.

Visiting Giza Today: Practical Context

Understanding environmental influence enriches any visit to the Giza Plateau.

When to Visit

- October to April offers milder temperatures (15–25°C).

- Summer months (June–August) can exceed 40°C and are physically demanding.

Best Time of Day

- Early morning or late afternoon for softer light and reduced heat.

- Sunrise offers atmospheric contrast between desert plateau and urban Cairo skyline.

Hydration & Protection

- Bring water, sunscreen, hat, and breathable clothing. The plateau offers limited shade.

Look Beyond the Monument

Notice the plateau’s elevation relative to the Nile Valley.

Imagine ancient water channels closer to the site than today’s river course.

Visit the Solar Boat Museum to understand river symbolism and engineering.

Nearby Additions

- Explore Saqqara to see earlier pyramid experiments.

- The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) provides broader Old Kingdom context.

Approach the site not just as an architectural marvel—but as a landscape story.